Released - March 1968

Genre - Psychedelic Rock

Producer - Frank Zappa

Selected Personnel - Frank Zappa (Guitar/Piano/Vocals/Effects); Jimmy Carl Black (Drums/Trumpet/Vocals); Roy Estrada (Bass/Vocals); Billy Mundi (Drums/Vocals); Bunk Gardner (Woodwinds); Ian Underwood (Piano/Woodwinds); James Sherwood (Saxophone)

Standout Track - Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance

In my previous review, for the Incredible String Band's The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter, I mentioned the surprisingly refreshing experience earlier this year of rediscovering what it's like to listen to music that sounds genuinely weird and unlike anything I'd heard before. Years of listening to prog rock had slightly dulled my ability to really give much credit to self-consciously eccentric music, but this year a few artists managed to surprise me for the first time in ages. One was the Incredible String Band, but the more prominent one was the Mothers of Invention, Frank Zappa's backing band from the mid-to-late 60s. Zappa's become a new favourite of mine this year - his combination of pompous hard-rock virtuosity, complicated musical innovation and experimentation and tongue-in-cheek sense of humour, verging on an almost self-destructive impulse to take the piss out of everything he's doing, all appealed to me massively, but it was his early stuff with the Mothers that actually struck me as wholly unlike anything I'd heard before rather than his later solo stuff. His early 70s jazz fusion instrumental work was broadly similar to some other prog rock/jazz fusion stuff like Focus, while his more conventional mid-70s art rock stuff was like a more self-aware version of a number of some of the more out-there prog bands, while also anticipating the mutant blues and savage, nonsensical primal content of Tom Waits's 80s output.

The stuff with the Mothers is very different, in that there's not a great sense yet of Zappa as musician, something that would come to the fore in his solo work, which put so much emphasis on virtuosity and complex arrangements. Here, instead, it feels like what Zappa is most interested in is simply exploding his imagination onto a record and using unusual recording and production techniques to create something truly alien-sounding. The unusual guitar techniques and firebrand solos he would become known for are nowhere to be seen, the musical performances fairly restrained, but the sheer weight of weirdness loaded onto the record more than makes up for it. I find it difficult to really think of the Mothers of Invention as a band in the conventional sense, rather as a specific period of Zappa's own experiments - in the mid-70s he would resurrect the Mothers as a brand new band on albums like One Size Fits All, but its lineup was completely different, with himself being the only consistent element, which suggests to me that the whole set-up wasn't a band that relied massively on the contributions of its individual members, rather that it represented a particular context and method of working that Zappa occasionally found conducive to making good work, regardless of who was actually involved in it. Furthermore, the mess of sounds on show on We're Only In It For The Money is so convoluted and so overwhelming that we're never really listening to the contributions of its band members, trying to single out Roy Estrada's bass or Ian Underwood's piano, we're just listening to Zappa's bizarre mind being splattered all over the blank canvas he gave himself.

The Mothers of Invention had been founded in 1964, simply called the Mothers, and had started gigging on the LA scene, where they attracted the attention of manager Herb Cohen and producer Tom Wilson, already a legendary figure as one of Bob Dylan's producers. Wilson had signed the Mothers (then renamed the Mothers of Invention to avoid any potential confusion that their name might be seen as an abbreviation of "motherfuckers") on hearing their first single "Any Way The Wind Blows," a pleasant, faintly twee bluesy pop song, and only realised after granting them a double album (the second one ever after Dylan's Blonde On Blonde) that he had something far more unpredictable and strange on his hands. Their debut album, Freak Out!, has moments of genius but is overlong and it never quite feels like Zappa has been given the opportunity to really indulge his imagination.

The same can't be said for We're Only In It For The Money, which was part of a four-part cycle of albums the band recorded after relocating to New York. The four albums formed a grander project that Zappa called No Commercial Potential, also consisting of the albums Lumpy Gravy; Cruising With Ruben And The Jets and Uncle Meat. Zappa explained that the tapes for the four albums could have been slashed up in completely different places, rearranged and reassembled in a different order and it would still have made one grand, unified work, and all the music belonged to the same project. That remark, I feel, is the key to understanding We're Only In It For The Money. This isn't an album where we're necessarily supposed to really enjoy the songs themselves for their own merits, rather we're supposed to sit and be overwhelmed by the strange and discomfiting experience of listening to all these fragments of sounds and ideas and, occasionally, music, being spliced together and ripped apart and thrown in different directions, thus granting us an insight into one man's sonic experiment.

The groundwork for this experiment is established in the very first track, "Are You Hung Up?" in which we hear engineer Gary Kellgren whispering into a microphone about how Frank Zappa is in a control room listening to everything he says. Suddenly the sound is ripped away and we hear percussionist Jimmy Carl Black remark "Hi, I'm Jimmy Carl Black and I'm the Indian of the group," a remark repeated later in the album. From there, the entire album dissolves into a continued pattern of never settling into one idea, constantly dissolving into fragments of dialogue and bizarre sounds, be it the astonishing sped-up monologue of "Flower Punk" in which Zappa rails about the idea of being a rock musician and the falsehood and phoneyness of the whole process - "The youth of America today is so wonderful and I'm proud to be a part of this gigantic mass deception" - to the horrible gabbling sound in the closing seconds of the musique concrete sound collage of "Nasal Retentive Calliope Music."

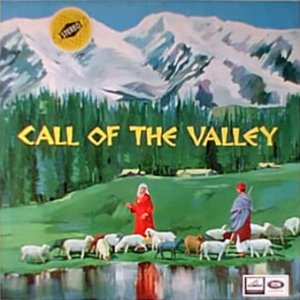

The album's sense of total entropy actually acts as a satisfying mirror to its political message that it occasionally tries to foreground - Zappa was hugely dismissive and cynical about the hippie and pschedelic movement of the mid-to-late 60s, despite the fact that his own music was often labelled as such. He felt that any attempt to try and instigate a mass movement built on trying to position oneself as an outsider was inherently stupid and counter-productive. He was certainly not an establishment figure, and the first proper song, "Who Needs The Peace Corps?", effectively mocks both the savagery of right-wing politics and the short-sightedness of left-wing politics - "I will love everyone, I will love the police as they kick the shit out of me on the street." "Flower Punk" similarly makes fun of the hippie flower-power movement. The album's title emerged late in its production after the release of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Zappa saw the Beatles as the epitome of everything he hated, the trend of trying to package outsider, counter-cultural movements into a commercial, sellable product, and so the album's artwork became a pastiche of the iconic Sgt. Pepper's cover, and its title became a parody of making music just for financial reward. The album's content, meanwhile, becomes not just a collection of disarming nonsense but an attempt to make something truly alternative, truly representative of outsiders and freaks and weirdos that don't fit into any cultural movement. Zappa is more artist here than musician, trying to make something truly representative of the chaos inside his head rather than trying to make great music people will buy.

There are moments on the album where the Mothers hit upon a genuinely compelling musical idea - the stately waltz of "Concentration Moon" and the doo-wop parody of "What's The Ugliest Part Of Your Body?" are great fun (doo-wop was one of Zappa's favourite musical styles, and pretty much every Mothers album contains at least one attempt to parody it), and "Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance" is easily the highlight of the album, a pounding, almost tribal pop song compelling the listener to really try and invite freedom into their lives. By and large, though, any attempt to try and talk about these songs as though they're real songs is futile and missing the point entirely. Usually, no sooner has the band alighted upon a decent tune than it's discarded and replaced by some discordant noise like the closing piece of musique concrete "The Chrome Plated Megaphone Of Destiny." This is never more true than on the album's other most tuneless track, "Nasal Retentive Calliope Music," which consists of a few minutes of random sound effects culminating in what sounds like it's going to be a genuinely enjoyable piece of surf music which is abandoned after literally about three seconds.

I've not yet listened to the other three albums that form the No Commercial Potential project, though presumably they consist of similar fragments and scraps of non-music and occasional genuine songwriting. I don't know if one really needs to listen to all four to appreciate what Zappa was doing - We're Only In It For The Money more than stands on its own as an artistic triumph, a total piss take of music-making for commercial gain, of trying to turn outsider-ism into something easily condensed and defined. At some point after the completion of the project, Zappa presumably became more interested in musical experimentation and in considering himself as an actual musician, and started working on solo projects that were very much built around complicated, symphonic songwriting rather than on production techniques and artistic expression. Personally, as a big lover of experimental music, I much prefer his solo symphonic prog rock stuff to the tuneless sound collages and general weirdness of his early experiments with the Mothers of Invention, but they're a fascinating and hugely enjoyable example of what the man's attitude and ideological approach to music-making was that grounds his later work wonderfully. Zappa would continue working with the Mothers of Invention until 1969, when he would disband them due to financial strain and continue working solo. As mentioned before, he would later resurrect the Mothers as a band name for occasional projects in the early 70s, but by and large it was an entirely new band with only the occasional guest appearance from older stalwarts like Ian Underwood. For the most part, though, Zappa's work going ahead would rightly place its entire focus on himself rather than pretending to be the work of an entire group.

Track Listing:

All songs written by Frank Zappa.

1. Are You Hung Up?

2. Who Needs The Peace Corps?

3. Concentration Moon

4. Mom & Dad

5. Bow Tie Daddy

6. Harry, You're A Beast

7. What's The Ugliest Part Of Your Body?

8. Absolutely Free

9. Flower Punk

10. Hot Poop

11. Nasal Retentive Calliope Music

12. Let's Make The Water Turn Black

13. The Idiot Bastard Son

14. Lonely Little Girl

15. Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance

16. What's The Ugliest Part Of Your Body? (Reprise)

17. Mother People

18. The Chrome Plated Megaphone Of Destiny