Released - November 1970

Genre - Folk

Producer - Paul Samwell-Smith

Selected Personnel - Cat Stevens (Vocals/Guitar/Keyboards); Alun Davies (Guitar); John Ryan (Bass); Harvey Burns (Drums); Del Newman (String Arrangements)

Standout Track - Father & Son

Cat Stevens's decision in 1969 to negotiate his way out of his contract with former label Deram had been a big gamble - with them he had achieved notable success as a pop act, but was feeling increasingly frustrated with his lack of freedom to flex his creative muscles. At the time, the notion of the singer-songwriter was still a fairly new one, and there wasn't necessarily any real precedent for his belief that he would be more successful going for a simpler, more folk-oriented sound rather than simple pop. But 1970's Mona Bone Jakon had seen that gamble pay off - "Lady D'Arbanville" had been a successful single (rather bizarrely, given that it's by far one of the worst songs on the album), and the album as a whole saw Stevens receive critical appreciation as an artist for the first time. So it was that for his next album he decided to continue down the same folk-rock, singer-songwriter vein.

The song that catapulted Tea For The Tillerman into global success was "Wild World," another song to deal with his breakup from longterm girlfriend Patti D'Arbanville, and one of the album's most memorable and catchy tunes, despite its lyrics of uncertainty and self-doubt as relationships fall apart and people are left facing the vagueness of an open future. Overall, this album is all about looking ahead at the future, from the trembling sense of unease in "Wild World" to the rebellious recklessness of the young protagonist in "Father & Son," or the jubilant celebration of a journey towards fulfilment in "Miles From Nowhere" or "On The Road To Find Out," following on from the first suggestion of Stevens's yearning for spirituality first glimpsed in "Fill My Eyes" earlier the same year. But despite his youth and being only at the start of a promising career, Stevens is very different from the headstrong young man sketched in "Father & Son," and knows better than to make an album that does nothing but celebrate or explore the beginning of a journey. In "Father & Son" alone, the balanced, more experienced voice of the boy's father (distinguished by Stevens by the brilliantly simple device of singing the father's part in a baritone voice and the son in tenor) is there to temper the young boy's recklessness, to counsel him to take time and take more pleasure in the simple aspects of life. Similarly, songs like the beautiful "Where Do The Children Play?" look backwards rather than forwards, reflecting on the enormous changes in society - the onset of war, overcrowding and environmental pollution, simply questioning where the children can play in the new modern world that mankind is building.

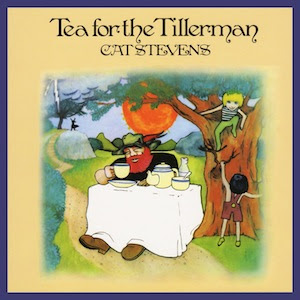

There's a wonderful spirit of childhood innocence that abounds throughout Tea For The Tillerman, with the notion of children's play being at the very heart of that opening track. The artwork, painted by Stevens himself, is gloriously childlike in its composition, while a number of the songs use effortlessly simple, hummable melodies almost akin to children's song (the "Hey" sections of "Where Do The Children Play?" is particularly sing-along). But it's by no means childish or simple music. Having forged a successful partnership with producer Paul Samwell-Smith on Mona Bone Jakon, Stevens kept the same musical team around him a second time around, particularly second guitarist Alun Davies, who would go on to become his closest collaborator in ensuing years. Davies had initially been brought in as a session musician for one album, but had been such an integral part of crafting that album's sound, and had shown such professionalism and dedication to the project, that Stevens had quickly recruited him again. The guitar styles of the two complement each other perfectly, and there's a real richness to the sound here that serves the pair of them well, tastefully augmented by John Ryan's subtle bass lines and Del Newman's simple string arrangements, which steer clear of the overbearing nature that made them so intrusive on Stevens's early work.

Tea For The Tillerman became an enormous global success, and the track listing reads like a Best Of compilation, containing a huge amount of Stevens's best-loved songs. "Father & Son" is effortlessly beautiful, and the final strains of "Tea For The Tillerman" serve as a wonderfully simple final prayer for equality and provision for all people. Its simple innocence and purity of spirit also keeps it all just on the right side of straying into being corny - these songs of childhood innocence and social observation never tip too far into feeling forced or contrived, but merely serve to conjure up one of the most gloriously heart-warming folk albums of all time. It would serve to be a formula that would continue to serve Stevens well for several years before again feeling the need for a change in direction.

Track Listing:

All songs written by Cat Stevens.

1. Where Do The Children Play?

2. Hard Headed Woman

3. Wild World

4. Sad Lisa

5. Miles From Nowhere

6. But I Might Die Tonight

7. Longer Boats

8. Into White

9. On The Road To Find Out

10. Father & Son

11. Tea For The Tillerman